From the earliest humans to Indiana Jones: Raiders of the Lost Ark

Stories and adventures from the world of archaeology 🏺📜⛏️

I began my archaeology studies in 2025, and much of the first year has focused on the foundations of archaeology, particularly world archaeology and the period BCE (Before the Common Era).

So far, I am absolutely loving it!

What fascinates me most is the sheer breadth of the subject. Archaeology ranges from hard core science, such as isotope analysis for radiocarbon (Carbon-14) dating and human osteology (the study of skeletal remains), to stratigraphy, which examines layers of soil and sediment at archaeological sites. Alongside this, we explore prehistory and ancient history, weaving scientific methods together with human stories.

A major focus has been the archaeology of human evolution. We have studied the earliest hominins (humans and chimps), our close relatives Homo neanderthalensis (Neanderthals), and modern human species, Homo sapiens, who evolved in Africa around 300,000 years ago.

It is an extraordinary evolutionary journey.

In his great book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, Yuval Noah Harari highlights the dramatic growth of human populations and power. Around 1500 CE (Common Era), the global population consisted of c. 500 million Homo sapiens. By the end of 2025, this figure had risen to a staggering c. 8.16 billion Homo Sapiens.

Global economic production shows a similar pattern of growth, from a GDP of roughly 250 billion US dollars in 1500 CE to around 117.2 trillion US dollars today at the end of 2025. These figures underline the scale of technological, scientific and economic development within the modern capitalist world.

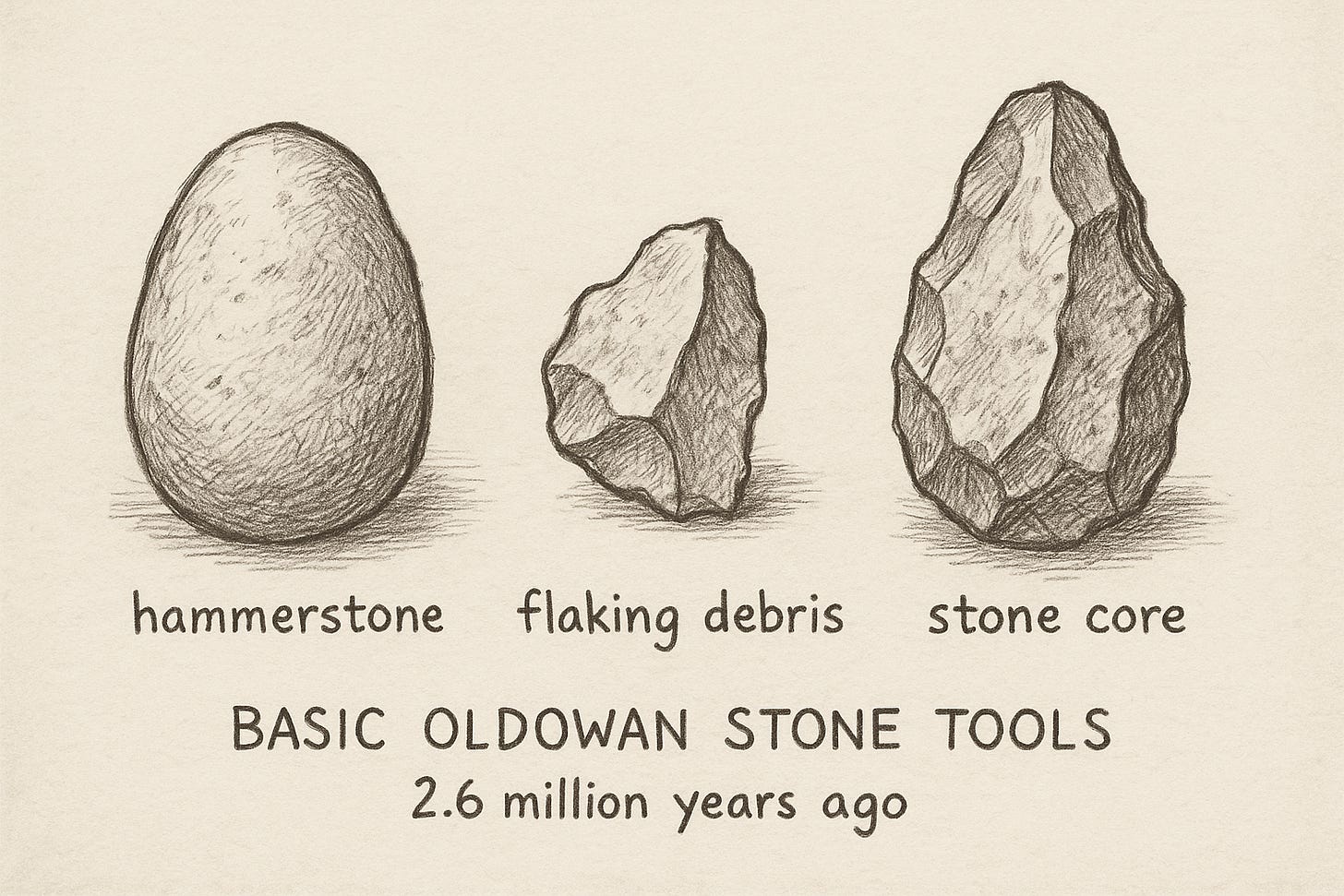

Some of the earliest human technologies were the first Oldowan stone tools (or industry), dating back around 2.6 million years. These were simple tools: hammer stones, stone flakes and cores.

Early hominins were also bipedal (able to walk) and appear to have controlled the use of fire as early as 800,000 years ago. Fire was a revolutionary technological breakthrough, providing warmth, protection, cooked food and social spaces for communication and bonding. Recent archaeological discoveries in the United Kingdom continue to refine and challenge our understanding of this period.

Our archaeology studies also took us through parts of human prehistory up to around 3000 BCE, when writing systems emerged and recorded history began. Alongside this timeline, we explored key archaeological methods and approaches.

Know someone interested? Share this blog with a friend who likes archaeological stories.

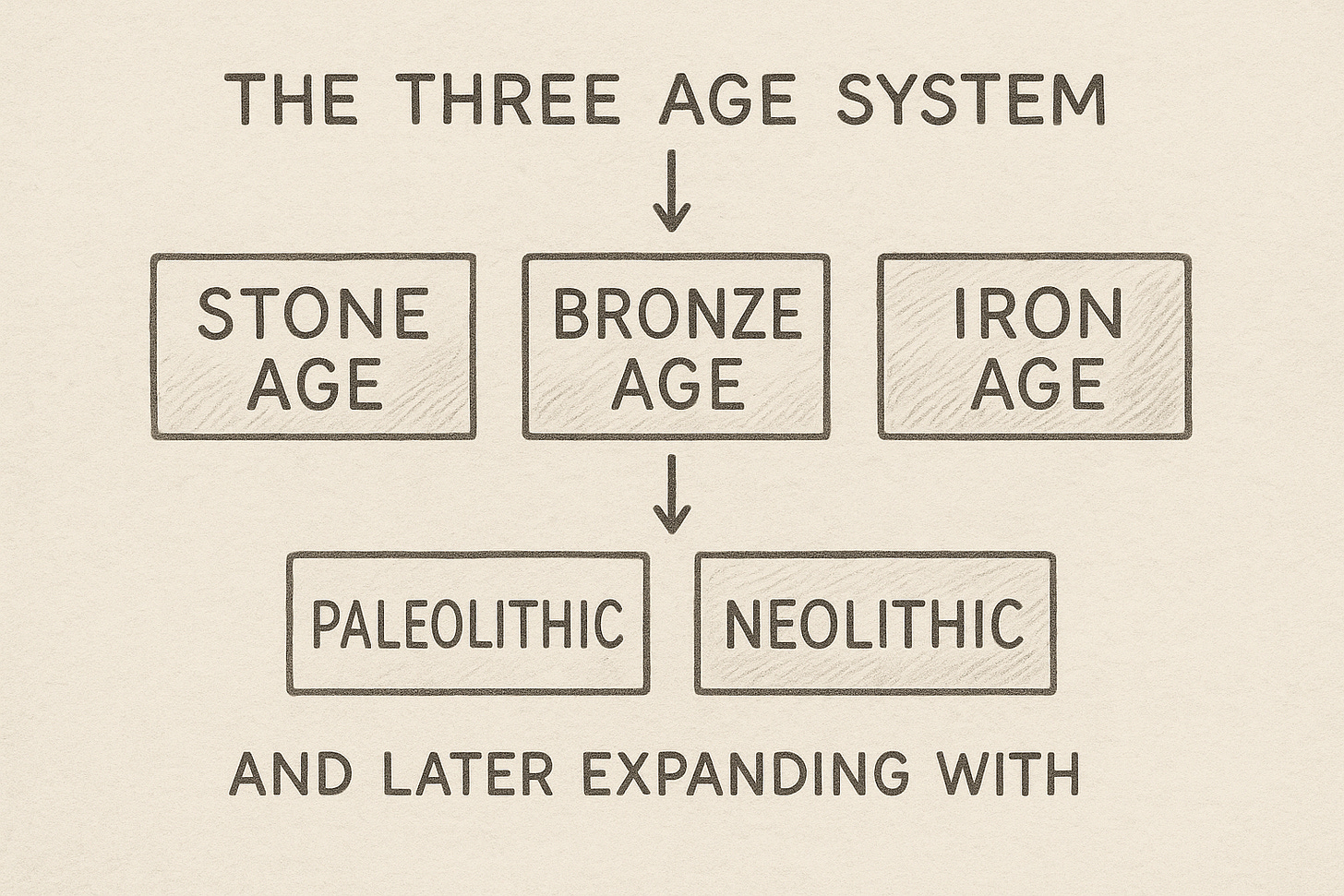

One important framework is the Three Age System, developed by Christian Jürgensen Thomsen while he was curator of the National Museum of Denmark in the early nineteenth century (between 1816-25).

The Three Age System divided prehistory into the Stone Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age, based on the dominant materials used for tools and artefacts. While simplified and largely Eurocentric, it laid the foundations for modern archaeological classification and typology.

As a Dane, it has been particularly interesting to engage with this aspect of my own national cultural heritage.

The British archaeologist John Lubbock (known for his big contributions to establishing archaeology as a field) later expanded this system in 1865 by dividing the Stone Age into the Palaeolithic (Old Stone Age) and Neolithic (New Stone Age). These distinctions allowed for a more nuanced understanding of technological and social change over time.

This framework immediately brings to mind popular culture and old movies.

In the opening scenes of the iconic movie Raiders of the Lost Ark, Indiana Jones just barely escapes a rolling boulder after attempting to remove a sacred artefact. That leads to the indigenous people throwing spears and shooting poisonous arrows at him in his attempt to escape.

Later, he returns to the university to teach archaeology, writing the term Neolithic on an old blackboard with his chalk, while explaining its Greek origins: neo meaning new, and lithic meaning stone.

It is a great moment where Hollywood and reality overlaps with the correct terminology.

Beyond tools and technologies, we also studied prehistoric art. This includes body art, parietal (cave) art and mobiliary art, which refers to portable objects.

On a family trip to Malta last year, I visited the National Museum of Archaeology and was struck by its Neolithic collection.

The figurines and decorated pottery, often made from limestone, demonstrated how central this material was to Maltese art and monument-building. It is a museum I would highly recommend visiting.

Now, in 2026, the next modules begin in February: Archaeology CE and Introduction to Classical Archaeology. These will complete my first year of studies.

In June, I will also be travelling to Leicester to take part in a field school, one of the most exciting and essential aspects of archaeology. Fieldwork provides hands-on experience on active excavations and research projects, allowing us one week to build a wide range of professional archaeological skills and experiences.

The field school will be led by archaeologists from the University of Leicester, in collaboration with their commercial unit, University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS).

I am very much looking forward to sharing stories and insights from the field in a future post.

Until then, I wish you a very Happy New Year filled with curiosity and adventure.

Best, Christian